Squeaky Wheel and Maccima Games teams celebrating the contract signing. Will the happy times last?

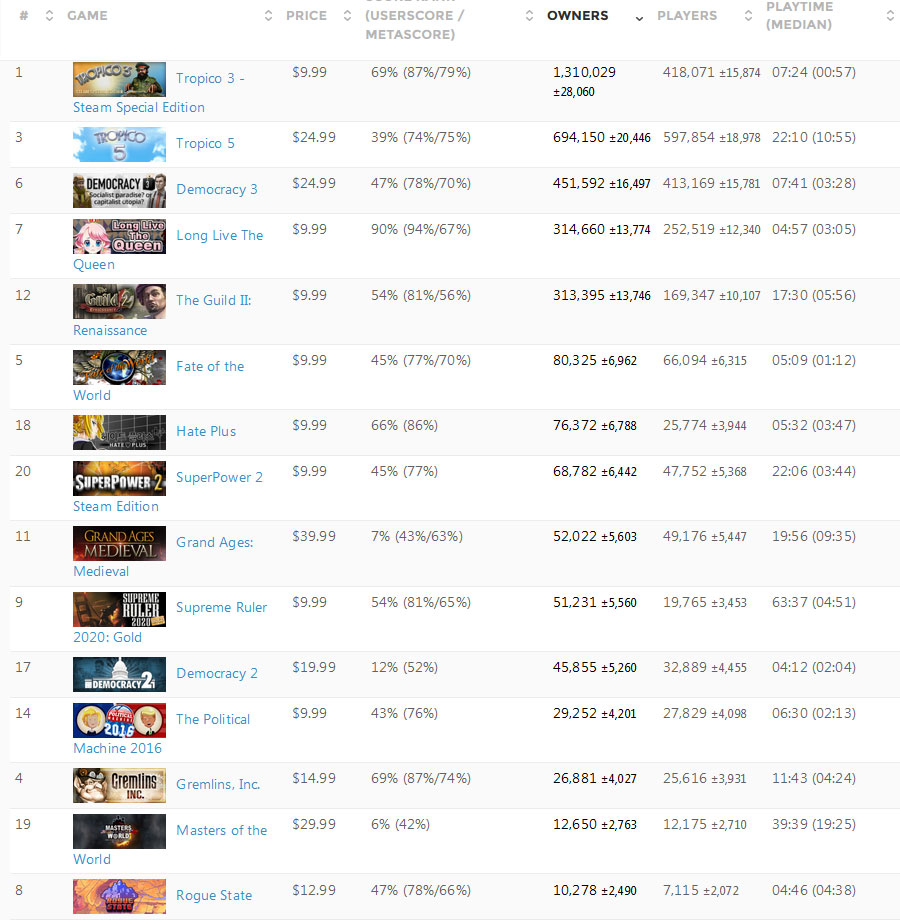

Publisher and developer relations have always been fraught with peril. There is a natural imbalance that occurs when a much more experienced entity with capital deals with a financially naive developer that wants to put their art out into the wider world. Recent news has borne this out, as I have heard of another publisher mistreating or wilfully misleading a developer. The point of this article is not to name and shame (and honestly, depending on when you actually read this, I could be referring to an issue from 2019 or from 2022), but rather to show what a healthy publisher/developer relationship can look like. I will also be providing actual contract details for Ruinarch (wishlist now!) to serve as a datapoint, as I believe information asymmetry is one of the key issues that leads to developers being taken advantage of.

First off, let’s define our terms.

Publishing

A publishing deal is one that first and foremost provides funding. For absolute clarity, I will refer to any deal that offers no money as “distribution” which I will describe later. I am aware that others may disagree with my definition, but I believe it is important for developers to hold that distinction in mind.

Aside from capital, a publishing deal typically also offers knowledge sharing and advice. This means advice regarding all aspects of game development, from programming to marketing. This is most useful for a first time developer, but even accomplished developers derive value from having a new set of eyes on their game.

In exchange for capital and information, a publisher will typically ask for profit sharing based on revenue generated after they recoup their costs. Basically, since they fronted the money, they want to be assured that at the very least, they will be able to recoup the risk that they took spending that money in the first place.

This profit sharing agreement can take many forms. For example, the publisher could ask for a 75/25 split on revenue until they have recouped their costs, and thereafter the split is 50/50. For our own deal with Maccima (as I’ll discuss later) we get a 100% recoup first before splitting the deal 70/30 in favor of the developers.

Distribution

A distribution deal is one that provides no funding, but basically provides marketing and distribution support in exchange for revenue.

I am personally quite wary of distribution deals. The up front money from a publishing deal establishes “skin in the game” for the publisher. As a developer, I am also more appreciative of the up front money because it immediately takes a lot of the risk off the table and lets me make the game without fear. A distribution deal feels to me like I have taken most of the risk by making the game on my own, then someone is going to come in at the tail end of the process and take some of my hard earned revenue.

However, to paraphrase Shark Tank , “70% of a hundred thousand dollars is better than 100% of 0 dollars”. There are many reasons why you would want to take a distribution deal:

You are a developer that just hates everything to do with marketing and money and you want to hide in your room and code all day.

You trust the people behind the distribution deal, and they are up front with exactly how much money they are planning to spend on marketing (this shows skin in the game).

You already have an established game and want to expand to a market that you are not familiar with, like China or the console market.

These are all valid reasons to accept a distribution deal. As a developer you will have to make the hard decisions about whether or not a deal is suitable to you.

First Contact

Publishing deals can take a long time to negotiate, and there is a lot of wooing that happens even before the first draft of the publishing deal is presented to you. Before we secured a deal for Political Animals, I had written on and off to Positech Games about the possibility of a publishing deal. Cliff brushed me off the first few times, but I eventually wore him down (politely, mind you), and in a meeting at EGX in 2015 where I presented him the current prototype of the game sealed the deal.

I first noticed and reached out to Maccima Games on February 9, 2019. Soon after, I visited them to try to get a better idea of the team and how serious they were with the game. I broached the idea of possibly publishing the game, but also told them that if they wanted to try for a bigger publisher (eg Paradox Interactive), I would use my digital rolodex on their behalf and try to secure interviews for them. Early on I already established that no matter what happened I wanted to help them succeed, which helped to build trust between us.

The Pitch Deck

A few months later I invited Maccima to an invite-only PC dev session with some other local devs, where we would get to show each other our games and give each other advice. I chatted with Marvin, the head of Maccima, to get a sense of where they were in development. I explained to him how much money in the bank we had, and how I’d approach a publishing deal. He told me that they were still interested, and were now preparing a pitch deck for publishers in general.

I have written about what should be in a good pitch deck before, and Maccima’s pitch deck nailed the most important parts. It was solid, and their expectations were reasonable. Most importantly, the amount they were asking for was something that we could afford. After reviewing our finances with our COO (wherein we definitely answered the question of whether we could afford this risk), we decided to offer them a contract.

Here is a link to Ruinarch’s (formerly World’s Bane) Pitch Deck, with financial data removed as requested by the developer.

The Contract

Finally, here’s the main event, a copy of the contract in place between Squeaky Wheel and Maccima Games. One of the nice things about being a small indie dev/publisher is it allows us to share things like this without dealing with a large bureaucracy. I made sure to ask permission from my cofounders as well as Maccima games, and would not be sharing this otherwise.

It’s important to note a few things. This is not meant to be an example of the “best” contract, merely an example of an actual contract. What works best for us may not work for you. The point is to negotiate until you are comfortable with the contract.

This document is a copy of the original, with personal details, dates and actual dollar amounts removed. I have left the comments in to show that this contract was crafted after negotiation between the two parties.

In the following paragraphs, I will discuss some of the key parts of the contract that you should pay attention to when negotiating your own.

Sales and Rights

Sections 3 to 7 cover what the rights of the publisher are with regards to the game. For example, we wanted exclusive and worldwide rights to sell and publish the game on PC/Mac and Linux, extending to DLC. We have right of first refusal for any ports or sequel, but if we’re not interested, then the developer is free to shop the game around. It’s made clear that all business transactions must go through the publisher. So for example, on the off chance that Epic Games (ahem) wants to throw a bunch of money our way, they would be dealing with us, not the developer. As a courtesy to the developer they would be included in any discussions, but its important that there is only one point of contact in these kinds of decisions. There are also numerous protections for the developer, such as stipulations that we cannot create sequels, ports, or DLCs without the agreement of the developer.

Royalties and Recoup Rates

Sections 8 and 9 deal with the numbers. These sections get very detailed, and explain how much of the royalty goes to the publisher, how exactly those number are derived, and how the money will be transferred to the developer. There was a lot of clarifications involved in this section, as you can see from the comments. To protect the Developer, they will be given direct access to financial data (which we can do with Steam). In absence of that, we promise to share documentation of funds received.

Termination

This is maybe one of the most fraught parts of a contract, but also one of the most important. A publishing agreement is a relationship, and like all relationships, it can go sour. This section stipulates what should happen in that rare case, and it can be the key to an amicable separation or a messy divorce. There was also a lot of discussion here, but the basic agreement is that we can terminate the agreement if the developer continuously misses milestones. The developer can terminate the agreement if we continuously miss payments.

The most interesting part of this is subsection e, which states:

e) The Publisher agrees that Developer cannot be held liable for delays due to acts of god, sickness of key staff, and other events beyond Developer’s control.

This is something that the developer asked for specifically, and which I agreed to immediately. While we’re all in this business to make money, we must also remember that sometimes life happens, and we have to make room for that possibility.

Negotiate, Negotiate, Negotiate

If you leave this article with only one lesson, it is that you should negotiate. Contracts can be changed. There is no such thing as a one size fits all contract. It is the publisher’s best interests to not have changes made, because each change requires lawyers, which cost money. Any change in the contract may also affect their contracts with other developers, and so the costs cascade and increase.

But as a developer you must be comfortable going into this relationship, so if there is anything that really jumps out at you that you feel is unreasonable, ask for it to be explained and if necessary, changed.

Conclusion

We are not presenting this contract as the perfect contract by any means. In fact I suspect that the contract will be picked apart by developers, publishers, and especially lawyers for various reasons. Ruinarch is also still in the middle of development, so things can still go sour. We have already agreed with Maccima to extend development because the initial time estimates were a little too tight. Here’s hoping that we will still be friends come next year.

Our goal is that having this out there can help prepare other devs and prospective first time publishers manage their expectations and offer at least one data point for what an actual contract looks like. We also hope that both developers and publishers understand that at the end of the day, this is a relationship, and both sides need to make sure that even as they look out for their best interests, they must take the time to make sure they are on the same page. The best contract in the world cannot fix a bad relationship, but a contract dispute can be fixed by two people sitting across from each other and negotiating in good faith.

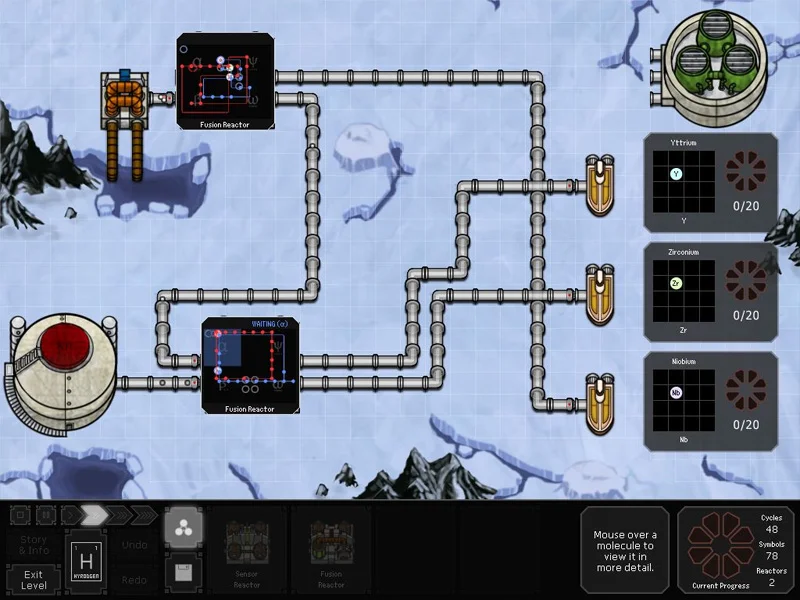

Thanks for reading, and hope you found this useful! If you want to support us, please wishlist Ruinarch.